The Thread Always Breaks: Review and Q&A for The Brittle Thread

By Danielle Levsky

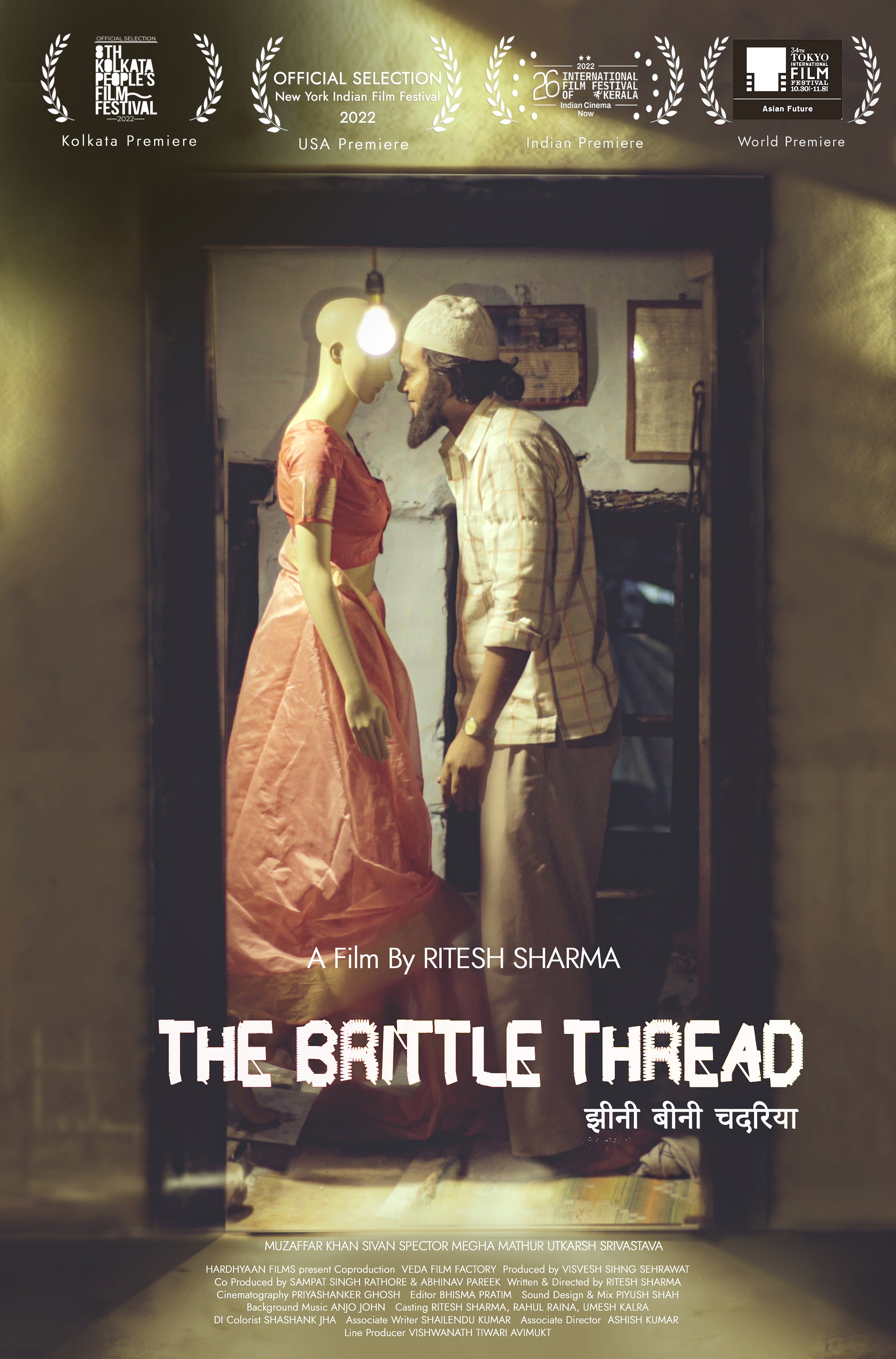

Ritesh Sharma's The Brittle Thread captures the intimacy and connection between disparate humans in an ancient city through its cinematographic perspective and astute storytelling.

Set in the ancient city of Varanasi, India,The Brittle Thread explores the lives of individuals who live out their stories amidst the increasing right wing nationalism dividing the population of India, which has threatened and continues to threaten the Muslim population of India. In particular, the film follows two different threads: the first thread is Shahdab, a traditional Muslim saree weaver, who meets and befriends Adah, a mesmerized backpacker from Israel; the second thread is Rani, a street dancer working tirelessly, and often dangerously, to care for her deaf daughter while maintaining a tumultuous relationship with Baba, a sometimes friend and sometimes frenemy.

Sharma’s direction draws the audience in by introducing the story from afar, as if we are ourselves travelers entering Varanasi. It begins with chaotic yet non descript visuals and intense music, then shifting into distant shots of a city alive and in motion. We see the weavers at work, their strings being pulled, like a moving painting. We see the main characters go through a daily routine, drawing us into the ritual and mundane of life in the city. Even watching the relationships between Adah and Shahdab, and simultaneously, Rani and Baba unfold is like watching a neighbor’s life through a window.

I spoke with director Ritesh Sharma Sivan Spector (Adah) about their work and journey through the making of this film:

The name “The Brittle Thread” is a fitting title for a story that follows characters with relationships hanging on by a brittle thread, the peace in Varanasi hanging on by a brittle thread, and the ways that all life intersects from culture to culture, religion to religion. What was the process for weaving together this story for you?

Sharma: I grew up watching Varanasi from the other side of the river Ganges in a calm suburb. The paradox of chaos and tranquility had always intrigued me: the noises of the temple bells, the conch-blowing during the aarti (prayers), the smoke from the cremations, and the steadiness of the river which flows undisturbed. The film was written during the period of my stay in the heart of Varanasi; all the characters, the scenarios, the political framework and the embroilment in the film are the result of my personal overview. The poet Kabir and playwright Saadat Hasan Manto inspired me; their ideals are strongly and deeply forged in my core beliefs and they emboldened me to tell my story, too.

The two main characters of the story, Rani and Shahdab, were the bottom line to weave the story. The dancers and sex workers performing near my village had always caught my attention as I was growing up, watching them dancing the whole night to entertain vulgar and disrespectful crowds for a smidgeon of what they deserve. Later, while meandering through the streets and narrow alleys of Varanasi, I found myself deeply in love with the process of weaving; the ancient art of producing sarees took me to the neighborhoods of the Muslim handloom artisans, who, ironically, make sarees that are worn by Hindu women. I witnessed their happiness and hardships. This story is my attempt to bring awareness to the conflicts and hatred, to give a voice to those no one hears, those that are invisible to the eyes of the government, while also praising the multicultural dimension of Varanasi and the whole country. This is my way of bringing change.

Spector: The way this story wove together was actually an amazing twist of fate, in my opinion. I had come to Varanasi because of my interest in the poet Kabir, who my character is based on in the film. I had also come to experience the legendary 30-day outdoor theater festival retelling of the Ramayana, which Varanasi is known for. I took a 26-hour bus ride from Kathmandu to reach Varanasi. When I arrived, it was so hot. Any native of Varanasi will tell you this is not surprising. But for me, in mid-October, arriving from the gentle mountain breezes of Nepal, I was shvitzing.

I had just said goodbye to my lover and was wandering the ghats of the city feeling lost and confused. I could feel the magic of the city buzzing around me but I could not access it. Then one morning, I bumped into an Italian woman at the hostel I was staying at, who began grilling me. Where are you from? Who are you? You are beautiful. What kind of European beauty is that? I began to explain that I am an Israeli, Ashkenazi Jew. She said, You need to meet my friend Ritesh. He is looking for someone to be in a film. Well, I said, I am an actress.

And so we met, and that evening Ritesh took me to a far away part of town to experience the amazing ritual of re-enacting the Ramayana in a huge outdoor festival ground. We had many deep emotional conversations. Ritesh and Megha Marthur nursed me when I got horribly stomach sick (this happens to many people who visit Varanasi. It happened to at least three or four of our actors/crew members when we were filming), and I decided to stay to film the movie. We discovered so many parallels between the oppression of Muslims in India to Palestinians in Israel. Ritesh helped me discover the magic of Varanasi, a place as crazy, holy, and conflicted as Jerusalem. I do believe that fate wove us together… and the experience changed my life.

Dancing plays such a vital role in this film. What relationship do you have to dancers, to dancing, and the way it is portrayed in this film by two of the main character women: Rani and Adah?

Sharma: I love dancing. Dancing is a beautiful expression for me. Adah, for me, is a free spirit, who dances the way she is. She just goes and dances in the festival. She also invites Shahdab to dance. Adah enjoys the moment and the music. She loves just how she is. She believes in living in the moment.

On the other side, Rani must dance in front of people to earn money and to survive. She is dancing to vulgar songs. She loves dancing, but she doesn’t want her daughter to dance. Rani also wants to work in film, and be an actress; she has dreams of leaving her profession.

Dancing makes both these characters strong.

Spector: From my experience with Adah, I see her as dancing through life. This is who I am when I am at my best - dancing. Not in the sense that I am always creating something beautiful, but in the sense that I am always attuned to the rhythm of life and it doesn't trip me up, but it propels me forward. The painful, the joyful, the messy are all part of the dance. That was what I loved so much about this character: she was like the most actualized version of myself, and spending a month living as her opened my heart to that rhythm of life.

For Westerners who may not be as familiar with the tensions of religion and culture within Varanasi in various parts of India, how would you frame the schism that is often created between Muslims and Hindus, rivaling political parties, temples and mosques?

Sharma: India is also one of the places in the world where there is a lot of Islamophobia; the current government is trying to make India a Hindu country. Anyone can relate because racism is everywhere in the world. We are against each other because of color, food, culture, and religion.

Why was it important for you to have an Israeli character, a Jewish character specifically, present in this film? What does this add to the story line?

Sharma: I wanted to talk about Palestine in this film. There are a lot of Israeli tourists and backpackers coming to India. I also wanted a Jewish girl in this film because I wanted my audience to understand that it doesn’t matter which country you are from, but what kind of person you are. It’s important to note that Adah is not religious herself. Adding a Jewish character shows a bigger picture of what’s happening in the world.

What was your personal experience in learning about the background of this story and what role you were asked to play in this woven web?

Spector: Ritesh introduced the film as based on an expression that goes something like this: "You don't know Varanasi until you know the prostitute, the bull, the ghat (stairs) and the saint." My character was meant to represent "the saint" - not in that I was preaching something characters didn't know, but that I had a different way of thinking. I think there is an interesting duality here, both because of India's history with British colonialism forcing new ways of being onto the country.

And then, there’s the beauty of travel and meeting people from other countries, which often does inject you with fresh ways of thinking and seeing the world.

Additionally, what was incredible in this process was that there was a huge emphasis on simply knowing your character's soul, and bringing ourselves to the film. The entire month we were filming I spent living as Adah. When I would meet new people, I would introduce myself as Adah. I spoke with an Israeli accent (which is not my natural accent at this point in my Americanization) all day long. Like her, I lived fearlessly, approaching people with love and curiosity, asking questions, meditating, going with the flow. It was as if by playing Adah, I was given permission to be stronger, less afraid, more open and confident. Through our filming process, I visited many incredible areas of the city, got to participate in several festivals and holidays, eat incredible food, and fall in love with Varanasi, and myself.

Were there surprising moments you discovered in your relationship to and playing with Muzaffar Khan (Shahdab)?

Spector: I would say the most surprising moment of filming with Muzaffar Khan (Shahdab) happened during the Deep-Diwali festival, which is an additional regional celebration of Diwali (there is another saying about Varanasi: "7 days, 10 festivals" and it's true).

We were filming a scene where we were supposed to be talking. As we were setting up for filming, we were sitting on ghat surrounded by people. At one point, two young men approached us and asked if they could take a selfie with me. I politely rejected them and continued talking to Muzaffar. Moments later, Ritesh approached these two young men and had an exchange with them in Hindi. Before we started filming, Ritesh gave Muzaffar a set of directions in Hindi that I couldn't understand. Then he turned to me and said, We're going to give you an excuse to say those bad words in Hindi that we taught you the other day.

That was the only direction I received before we started rolling. We were talking on camera, and then the two young men approached again. I assumed this was a set up, so went along with it, and again rejected their ask about a selfie. They began talking to Muzaffar, and I couldn't understand what they were saying. Suddenly, they began to hit him. I was completely shocked - it was completely real, not stage combat choreography. I immediately turned into the Israeli Krav Maga Badass that Adah is and began shouting at them in English, Hindi, and Hebrew, and at one point, slapping one of the men. The fight went on for several minutes, and then Ritesh called for us to cut. I looked up, and a huge crowd had gathered, who all erupted into applause.

It was definitely the moment where I have felt most badass in my life, as I have never gotten into a street fight before. Muzaffar was totally fine; they had not been hitting him that hard. In fact, the two men complained that my slap was the most brutal hit exchanged. I guess I don't know Adah's strength. Afterwards, we all took a selfie.

We are drawn in closer as the characters’ relationships develop, as questions of religion and politics are called into play. Spector’s Adah is a perfect inverse to Megha Mathur’s Rani. Both dance, though Adah dances with bliss and freedom, and Rani dances with fire and dedication. Spector portrays an endlessly inquisitive and thoughtful Adah, where Mathur wonderfully captures Rani’s coldness and warmth, sweetness and bitterness, compassion and defense. We learn quickly, through the rise and fall of connection, that relationships are the brittle threads in this city, extending further to the brittle thread of peace between Muslims and Hindus in Varanasi.

This thread snaps in the final denoument of the film, where a Hindu leader is murdered and a Muslim man is wrongfully blamed. In the last moments of the film, Varanasi is ablaze with fire, fueled by anger and fear.

The Brittle Thread expertly explores the complex connections between hardworking humans, who go into every interaction, every day, hoping that the thread will grow stronger.

The film is currently on the festival circuit, but you can read more about and anticipate its arrival to streaming services here.