The Many Faces Of Polly Jean: PJ Harvey’s Evolution in Fashion & Music

Over the course of nearly three decades, Polly Jean Harvey has morphed into one of pop culture’s most chameleonic forces. From a rabid “Joan Crawford on Acid” to a lace cocooned wartime poet and every archetype in between, Harvey’s style has evolved as much as her music throughout her storied career. A confluence of personal politics, self-awareness, and allergy to repetition, PJ Harvey’s artistic evolution has cemented her place as a fashion icon, feminist hero, musical dynamo, and pint-sized powerhouse.

With a keen eye for detail and a hard-wired aversion to litany, Harvey recruits a team of collaborators to realize each album’s unique aesthetic. Harvey’s braintrust, a group tasked with realizing the visual and aural styles of each album, boasts photographer Maria Mochnacz, cinematographer Seamus Murphy, producer Flood, and self-described “musical soulmate” John Parish.

A one-woman tour de force, the many faces of Polly Jean Harvey have defined an entire generation of outsiders, from sound to style.

“…Essential feminist distinction between egoist blurrier and honest irruption outpouring…and of course by her postrockist guitar, where she starts to reinvent her instrument the way grrrr-punks reinvent their form…” — Robert Christgau for ‘Village Voice’ (1992)

Every musician is afforded an entire lifetime to write their first album, and Harvey approached her band’s debut with the appropriate degree of intensity and austerity. Wholeheartedly believing that ‘Dry’ would serve as her first and last imprint in music, she poured all of her blood, agony, and ire into the 11-track LP.

Not only did the divinely abrasive album serve as Harvey’s grand entrance into the global rock scene, but it also introduced her feminist canon. The album’s most commercially successful track, “Sheela-Na-Gig,” was penned about eponymous exhibitionist statues scattered throughout the U.K. The raw and flayed track challenges the unrealistic expectations projected upon women and their resulting fits of self-loathing.

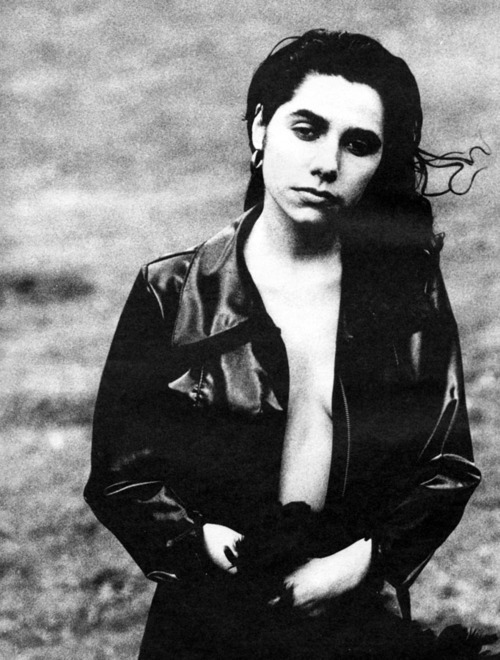

While fashion was not yet an element of focus in her art, Harvey expertly wielded her body as a manifesto early on. Around the time of her debut album’s release, Harvey ignited controversy with her first NME cover, which featured her topless, back to the camera and defiantly gleaning an unshaven armpit.

“I don’t even think of myself as being female half the time. When I’m writing songs I never write with gender in mind. I write about people’s relationships to each other. I’m fascinated with things that might be considered repulsive or embarrassing. I like feeling unsettled, unsure.” —PJ Harvey to the ‘Sunday Times’ (1993)

After a meteoric rise to the global zeitgeist and non-stop touring following the release of Dry, Harvey began internalizing all of the transgressions of fame. Drained by a tortuous stint living in London, a poor diet, relentless exhaustion, and a messy break-up, Harvey suffered a nervous breakdown that flung her back home to the countryside in Dorset. It was during her convalescence that she would pen Rid of Me a manic rumination on revenge, devotion, and self-preservation.

Drawing from the dynamism of performance art, Harvey crafted her most complicated songs yet atop a bedrock of unconventional time signatures and cavernous song structures. The title track—written in the crux of her mental unraveling—attacks masculinity with the mercy of a junkyard dog. With each track, Harvey just sinks her teeth deeper into the jugular.

This year marks the last for Harvey’s tried-and-true goth fashion sensibilities, mostly comprised of slim black turtlenecks and beefy combat boots. The album’s cover (shot in photographer Maria Mochnacz’s bathroom) piggybacked on the preceding year’s nudity “controversy,” showcasing a nude Harvey whipping talons of drenched hair across the stark, monochromatic frame. Despite outcry from Island Records, the warts-and-all photo served as the crowning jewel to some of the decade’s most love scorned songs.

“It’s that combination of being quite elegant and funny and revolting, all at the same time that appeals to me. I actually find wearing make-up like that, sort of smeared around, as extremely beautiful. Maybe that’s just my twisted sense of beauty.” —PJ Harvey to SPIN (1996)

After retreating from the spotlight for two years and using album royalties to buy a house in the English countryside, Harvey decided to part ways with her trio and go it alone as a solo artist with a little black book of collaborators. With Flood manning the boards to produce her swamp stomp blues masterpiece, Harvey ushered in her most theatrical era with To Bring You My Love. Harvey continued to wax poetic on themes like love and loss, this time adopting the perspective of a woman willing to sacrifice anything—and anyone—to satiate her carnal desires.

Despite never being baptized or immersed in religion, TBYML houses Harvey’s most spiritual imagery, rubbing elbows with Heaven, God, and Jesus Christ along her hedonistic warpath. These otherworldly subjects are complemented by expansive soundscapes speckled with bells, organs, vibraphone, and dueling guitars. Hell is other people, but for Harvey, it’s also where she finds the man she loves most.

Dubbed the “Joan Crawford on Acid” phase by Harvey herself, the TBYML era ushered in bawdy costuming, from show-stopping ball gowns and smeared makeup to hot pink catsuits and bouffant wigs. Harvey’s discomfort with fame manifested itself in her hyper-femme persona, and its contrariness only fueled the public’s fascination with the young songwriter.

Recorded during what Harvey refers to as an “incredibly low patch,” her fourth studio album is remembered as her most vulnerable work. A departure from her previous full-lengths, both lyrically and sonically, Harvey approaches her tried-and-true subjects of love and all the bullshit that comes with it from a landscape of keyboards, electronics, and acoustic guitar.

Many of her songs are told through a dominant female perspective, including the monstrous hit “A Perfect Day Elise.” As the first PJ Harvey album to have its lyrics printed on its sleeve, ‘Is This Desire?’ is pocked with emotional pinpricks and land mines alike, and no one is safe.

Remaining faithful to the album’s air of self-possession, Harvey’s fashion throughout the late ‘90s exemplified a woman becoming reacquainted with herself. Sporting Bettie Page bangs, mussed hair, and light-handed makeup, fans found Harvey in recovery from the bombastic ‘To Bring You My Love’ years as she ruminated on her next transformation.

STORIES FROM THE CITY, STORIES FROM THE SEA [2000]

Harvey’s jangling, howling interpretation of pop music was met with overwhelming acclaim and nabbed her the 2001 Mercury Prize. Stories greets a new collaborator in Harvey’s tight-knit circle of friends—Radiohead frontman Thom Yorke, who lent his trademark falsetto to the gossamer background of “Mess We’re In.” Power ballads like the gloriously billowing “Big Exit” and thumb thumping “Kamikaze” remind us that the trademark Harvey spunk is still bubbling beneath that freshly ironed pantsuit.

Trading primal rhythms and ham-fisted manifestos for slick urban landscapes and electro sheen, Harvey’s foray into the new millennium meditates on the dangers of modernization, the pangs of aging, and the incessant fight for individualism. With ‘Stories’ Harvey confirmed that she is one of the greatest artists of both her time and all time.

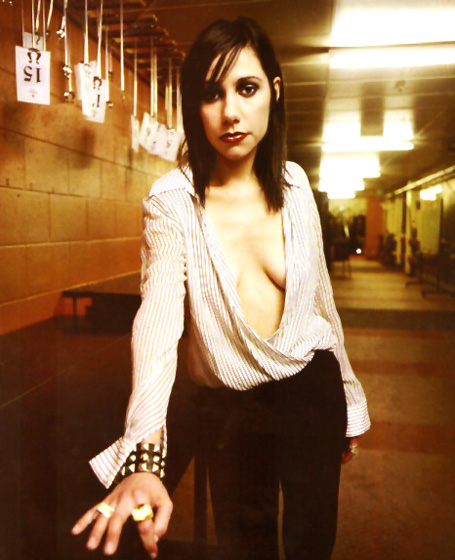

Harvey greeted the new century with a city slicker style that matched the sonic luster of her new sound. The album’s cover surmises her newly adopted Americanized aesthetic, wrapped in a couth black dress accessorized with a gold satchel and steely stare. Harvey also briefly revisited her exposed lingerie look of the mid-90s, this time utilizing dark tones and surprising pieces, like a glitter, transparent black turtleneck. Donning mostly monochromatic ensembles and contemporary silhouettes, Harvey flaunted her ability to adapt to the times, in respect to both her career and her closet.

Harvey took her hands-on approach to soaring new heights with her self-produced album ‘Uh Huh Her,’ opting to play every instrument (save for drums, a duty eventually relinquished to Rob Ellis). Recorded over the course of two years spent pin-ponging between East Devon and Los Angeles, Harvey’s restlessness is palpable amidst the album’s murky tales of displacement and dissatisfaction. Revisiting the dirt and grit of her breakthrough debut, Harvey harnesses the intimacy that made her such a wunderkind in the past in electrifying new ways.

Harvey dabbled with the punk aesthetic of her early days, hacking her raven locks into a textured shag and slipping into skimpy minidresses trimmed in garish colors. Though Harvey began to shed skin onstage and dabble outside of her elemental black-and-white getups, she would never trump the glamour of her mid-90s frocks.

The UHH period was a very self-aware one for Harvey, and it was reflected in the album’s packaging, whose inner-sleeve was decorated with a long set of self-portraits and handwritten annotations gleaned during the album’s recording process. These scribbles included notes like “Scare yourself,” “Too normal?” and “All that matters is my voice and my story.”

“I work on words, mostly, toward them being poetry or short stories, and then some become songs. They all find their place in the world, but they all start off in the same place…I’m not quite sure what the next project needs to be until it presents itself, and then I know. I just follow dutifully while I’m being led.” —PJ Harvey to The A.V. Club

After whispers of retirement rose to grumbles, Harvey defied naysayers and loyal fans alike with ‘White Chalk.’ Ditching her favored guitar for piano—an instrument that she was barely familiar with at the time—and the autoharp, Harvey cobbled together her bleakest songs yet. Striving to expand her oeuvre both topically and musically, Harvey weaves the history of her home country one bereft melody at a time.

Stemming from her learning curve with the piano, Harvey’s melodies are feather fingered and fragile. Trekking in the high end of her contralto range, Harvey’s voice sounds windswept and glassy, whether she’s lulling through a slow waltz (“Dear Darkness”) or echoing across a bed of reverb swaddled autoharp (“White Chalk”).

For the White Chalk era, Harvey continued her partnership with Maria Mochnacz’s sister Anna, which began during the Uh Huh Her tour. In order to bring Harvey’s concept of sprite poet to life, Mochnacz sourced her fabric from vintage shops and adapted 18th century dress patterns. The resulting frocks, through hardy and amor-like, were adorned with delicate details; one dress was stitched with snippets of Harvey’s lyrics, while another featured a hemline made of mirror shards. The fastidious costuming mirrors the theatricality of mid-‘90s Harvey while bringing her interest in her country’s roots to the forefront.

An album thriving on innovation and alternative history, Let England Shake is an epic triumph in Harvey’s robust catalog. A critical achievement, as well, LES nabbed Harvey her second Mercury Prize, making her the most successful artist in the prize’s history. In the album’s 12 tracks, Harvey assumes the role of wartime poet, retelling the history of her homeland, one that is tilled and toiled by the blood of its own.

Throughout the album’s arduous two-and-a-half year writing process, Harvey culled inspiration from poets including Harold Pinter and T.S. Eliot, along with Salvador Dali, The Pogues, and the Velvet Underground. She continued the vocal experimentation that began with White Chalk in order to reinforce her role as the story’s narrator, breaking free from the confines of character. Harvey’s fixation on politically charged subject matter (militarism, the Afghan War, the Gallipoli Campaign) and continued collaboration with cinematographer Seamus Murphy laid crucial building blocks for Harvey’s newfound journalistic approach to songwriting that would become fully realized with Harvey’s next release, ‘The Hope Six Demolition Project.’

Continuing to draw inspiration from fashion of centuries bygone, Harvey’s stage costumes were modeled after sensational Victorian fashion. Many of the tour’s pieces were designed by Ann Demeulemeester and were complemented by matching feather headdresses. Stiff and simple compositions, the ‘LES’ ensembles traded the filigreed armor of the White Chalk era for more simple and stunning machinations.

THE HOPE SIX DEMOLITION PROJECT [2016]

While weaving through Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Wasington D.C. alongside Seamus Murphy between 2011 and 2014, Harvey compiled material that would birth The Hope Six Demolition Project and a poetry book titled ‘The Hollow of the Hand.’ Harvey shook up her artistic method by opening her recording process to the public in the form of an art exhibition at London’s Somerset House (aptly dubbed ‘Recording In Progress’).

The album’s title is a reference to the HOPE VI housing projects, which Harvey saw firsthand while touring Washington D.C. alongside Murphy and ‘The Washington Post’ reporter Paul Schwartzman. The project is directly reference in the LP’s opener and lead single “The Community of Hope,” which drew hearty criticism from Capitol Hill. The entire of the THSDP is viewed through a voyeuristic perspective and focuses on relaying the stories of those affected by war in global landscapes previously unexplored by Harvey’s authorial gaze.

Harvey resurfaced in the limelight with a demure, all-black and navy wardrobe. Embracing her newly adopted citizen journalist role, her outfits enable her to settle into her characters’ landscapes and shirk any rockstar gleam. Sporting slim-cut blazers, long and unkempt locks, and lax silhouettes, Harvey’s new wardrobe bears an undeniable resemblance to that of her contemporary Patti Smith. While Harvey’s current fashion choices seem forgettable and homogenized, it is no doubt an integral facet of the next character—and world—she is striving to build one song at a time.