A New Love Poem for Our New Age: Alex Dimitrov’s Flowering “Love” and “Loneliness”

“I love anyone who cannot say goodbye.”

Alex Dimitrov

“What are you thinking now? / I am thinking that a poem could go on forever.”

This line closes out Jack Spicer’s poem, “Psychoanalysis and Elegy,”—a piece that New York-based poet Alex Dimitrov returns to frequently. Dimitrov, whose intimate poetry often explores the relationship between endearment and solitude, finds himself obsessed with this notion.

I am thinking that a poem could go on forever.

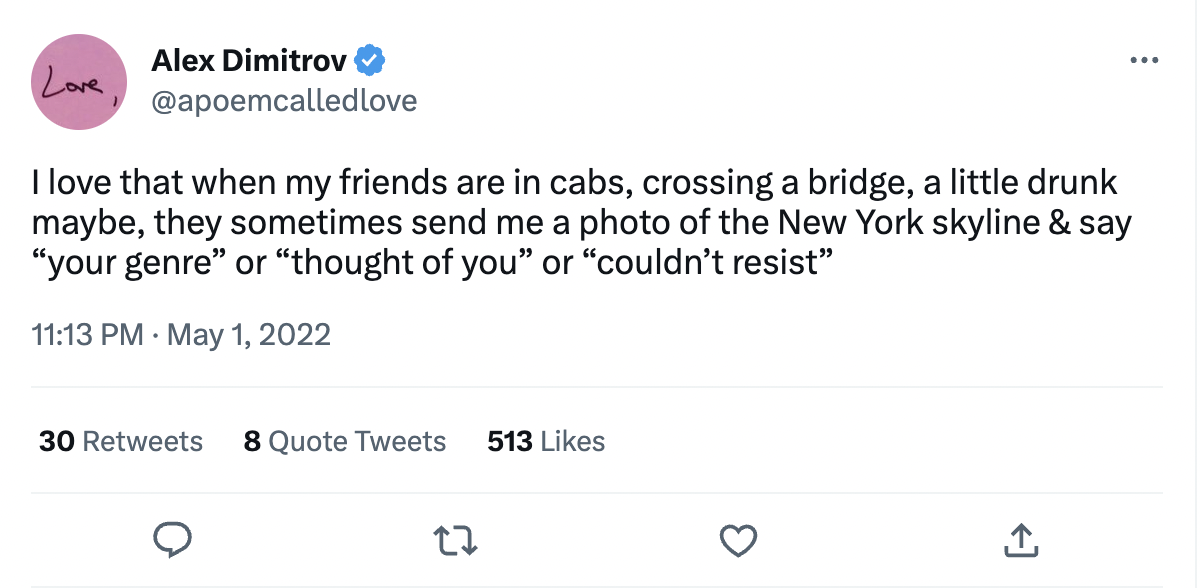

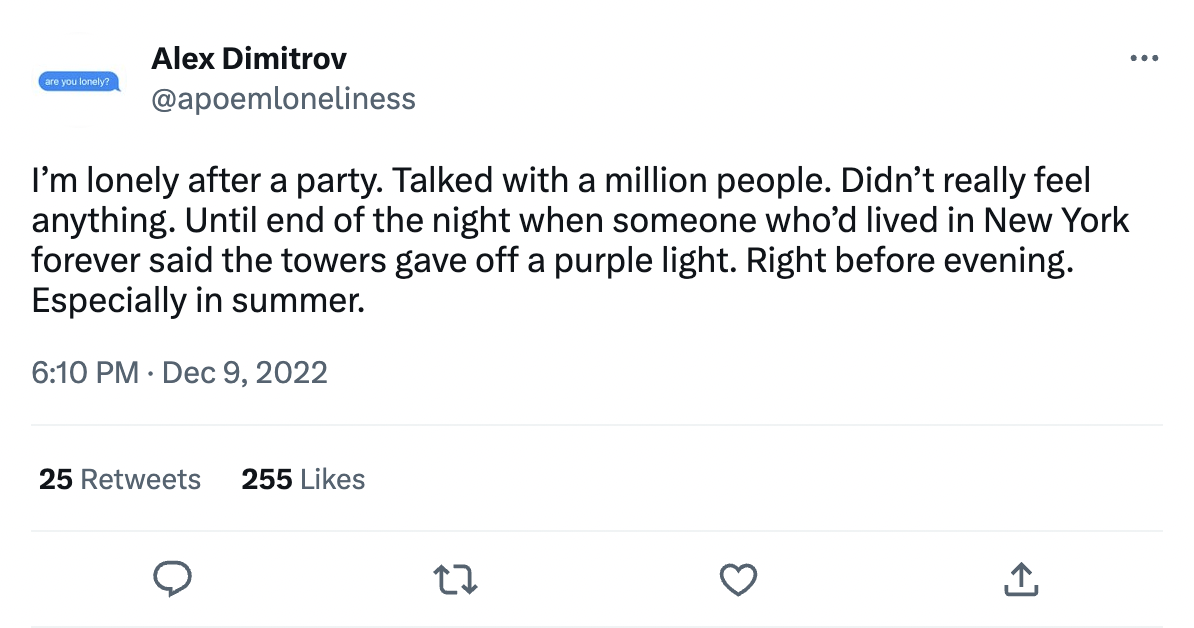

In his continuous poetry projects, “Love” and “Loneliness,” Dimitrov attempts just that—rejecting the limits of the page and debuting a bold, new approach to the poetic form. By using social media as the medium, Dimitrov adds new lines to these two poems at their respective Twitter accounts, @apoemcalledlove and @apoemloneliness, each day. “Love” has been ongoing since February 2020, just ahead of the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, while “Loneliness” got its start more recently in September 2021.

“I love people who continue / I love being known by one waitress at a diner / I love thinking of you last before I fall asleep,” writes Dimitrov in “Love,” over several days.

“Loneliness” mimics: “I’m lonely on a run & it’s the happiest loneliness / I’m lonely reading DMs in an Uber / I’m lonely but not as lonely as when I was fucking straight men.”

I spoke with Dimitrov over the phone to discuss these projects on an early warm day—the first warm day of the season. I was eager for the opportunity to sit on a park bench outdoors while we chatted, Dimitrov’s books by my side, and a view of the neighborhood blooming ahead of me. Our conversation began with the two themes that have been central to his poetry for years.

“I've been very lonely when I've thought I was in love with someone,” Dimitrov explained. “And when I’ve been with people I thought would make me less lonely, I've often felt my loneliest then. I've also felt my most fulfilled in the world, and in love with the world when I've been alone. There are some perfect days when you don't see that many people.”

The idea for the two corresponding projects, both love poems in their own right, came out of Dimitrov’s experience working on his 2021 collection, Love and Other Poems. The book is a masterful assembly of contemporary love poems that span from conversations with the moon on Fire Island to stream-of-consciousness recollections of crying publicly in the backseat of a Manhattan taxi. This collection notably features the poem, “Love,” which serves as the catalyst for the piece, still in-progress online today.

“I love you early in the morning and it’s difficult to love you,” he opens. The original poem sprawls for ten full pages, listing line by line a broad catalog of things that Dimitrov finds himself drawn to: Nina Simone, the impulse to change, everyone falling in love in Jane Austen novels, and more—line by line, ode by ode, each boast spilling over into another.

Finally, Dimitrov ends: “I love anyone who cannot say goodbye.”

I am thinking that a poem could go on forever.

Dimitrov refuses to say goodbye to the project of “Love.”

I first read Love and Other Poems in late summer, with Dimitrov’s poetry offering language to the fervent transition between hot sunsets and cicadas’ shouting, to the tumble of leaves and fall’s assertion. The printed version of “Love” is structured around the seasons. Each month of the year is mentioned in chronological order. A set number of lines follows routinely, and once December’s quota is met, the poem finishes. In the transition to its current continuous format, Dimitrov rejects this initial, self-imposed restriction.

“Before the book came out,” he says, “I thought: there's really no reason why I stopped writing that poem other than the fact that there was a deadline for a book. [...] The structure lends itself to continuation because it's so conversational and quotidian; and for me, there's an enjoyment in writing it. It doesn’t feel like other poems.”

This departure from the standard poetic form has forced Dimitrov to reconsider his own writing process. There are days when the next line feels obvious and comes easily. There are days when it doesn’t. On some, the world feels absent of love, and loneliness seems simple. On others, joy is so abundant that the idea of loneliness feels for a moment, impossible. Dimitrov’s commitment to writing these poems in perpetuity means that he’s had to encourage himself to look for love, and to consider loneliness intentionally.

When it comes to bringing these observations to the page (or laptop keyboard, restricted by Twitter’s 280 character limit), these poems have meant a deeper relationship to endurance and discipline: “Some days are a lot harder than others. Some days are so easy that I just want to keep going. But of course, the constraint is doing one line a day.”

“I’m lonely like the first night of fall,” Dimitrov writes in “Loneliness.” In “Love,” the following day, he builds: “I love walking home as the nights get cooler.”

By pushing beyond the barriers of the traditional poem, Dimitrov has not only crafted an original type of love poem for our new age; but he’s also allowed his writing process to include an epistolary exchange with readers. The online nature of the piece automatically resists loneliness. With each new tweeted line comes an onslaught of likes, retweets, and replies from eager followers keeping up with the poems’ development. On its own, “Love” has amassed upwards of 21,000 followers. “Loneliness” has over 5,000.

In our conversation, Dimitrov says that he loves “seeing certain tweets that I never would have imagined getting so retweeted. And then with other tweets, I’m like, ‘oh, this is a good one,’ and that tweet won’t get any attention.”

Though, audience reception isn’t why Dimitrov writes the line each day. He says that each tweet’s engagement comes as a surprise, but these tweets have allowed him to take the emotional pulse of the audience. These daily explorations into love and loneliness provide the audience with a reflective space in the otherwise chaotic landscape of the Internet.

In “Love” and “Loneliness,” I see my own emotions reflected, though also notice clear departures. These pieces are a reminder of the significance of our affinity, and of our individuality at the same time. Love poems have always made us feel less alone; though “Love” and “Loneliness” are a revolution in opening the form up to exchange and conversation between reader and writer.

I am thinking that a poem could go on forever.

In addition to Spicer, Dimitrov draws inspiration from poets such as Allen Ginsberg, Emily Dickinson, and Walt Whitman. All three are queer poets who resisted the confines of the traditional form in order to sing praises of the world around them. Whitman notably called out in “Song of Myself,” “Prodigal! you have given me love—therefore I to you give love! / O unspeakable passionate love!”

“People will read Emily Dickinson 500 years from now and still be able to understand the human voice behind that. People read Emily Dickinson now and are still able to understand the human voice behind that. [...] There's something about the human soul that Dickinson speaks to, that Whitman speaks to. No matter what changes in the culture, the human voice is always going to be something that is recognizable to people.”

Dimitrov views “Love” and “Loneliness” as a window into humanity today. He doesn’t know if our generation is particularly unique, though does think that today’s experiences offer something valuable: “People have experienced these two states of being throughout time—from the beginning of time, and they will until whenever our time on Earth ends. [...] The circumstances and the ways we’ve understood them have changed. [...] I'm hoping that these poems serve as an archive of what one person in the 2020s was feeling on this particular day.”

He writes in “Loneliness,” “I’m lonely & feel most American waiting to get paid.”

And in “Love,” “I love streaming Grimes in a Tesla.”

Today, these poems are contextualized by so much. Whether it’s our return to public community following pandemic-related isolation or a rumbling call for emboldened social movements driven by the heart, “Love” and “Loneliness” speak to our current condition. Even further, despite Dimitrov’s resistance to the seasonal structure of the printed version of “Love,” these continuous projects remain framed by the natural today, especially as each season becomes less predictable thanks to the threat of climate instability. I love the flowers, but I am lonely when I think about climate change.

“I do think that we oscillate between these extremes, especially now,” Dimitrov told me. “You can feel euphoric because of something online for two minutes, and then you can be completely down and out.”

Dimitrov says that developing “Love” during the onset of the pandemic gave him a comforting sense of routine, something that he valued as the world plummeted into strife and resistance during those early, uncertain months. “Loneliness” is being developed in reverse—a condensed, print version of the poem will be included in Dimitrov’s next published collection.

I am thinking that a poem could go on forever.

“I think that poems go on forever anyway, whether or not they're continued,” Dimitrov believes. “They go on in the consciousness and culturally and in a very real way—if they're good poems.”

As the weather in my own neighborhood tips unexpectedly towards early springtime rain showers and quick-flowering cherry blossom trees, I am thinking of a line from “Love” in Love and Other Poems:

“I love that we can fail at love and continue to live. / I love writing this and not knowing what I’ll love next.”

Today, I love poems that remind me of abundance even among absence. I can’t wait to see what I might love tomorrow.